Rest (for Tired Negroes) (2025-present) lays to rest bigoted tropes about Black bodies while honoring the fullness of Black lived experience. Over the past decade, I have collected dolls and collectibles depicting racist stereotypes of African American people. Some were found in my grandparents’ home after their death; others were given to me by thrift shop managers and individuals who wanted them removed from circulation and placed in the hands of someone who would use them with care and intention.

This work documents the first of these burials: a large handmade plush doll with exaggerated features common to American racist craft traditions. Now housed in its coffin, the doll is transformed through an act of reclamation—covered in an altar that honors a full human being. This project does not seek to erase history, but to acknowledge how these representations shaped our ancestors and, ultimately, who we have become—as, Maya Angelou would say, “the dream and the hope of the slave.”

Below are images of the final resting place of the doll along with the process pics building the custom pine and oak coffin in collaboration with Berkshires-based master woodworker, Jay Allard. Below, you can learn more about my inspiration for this first piece, Boston-based fiber artist and educator, Theresa-India Young, and view source materials from the special collections at the UMass Boston Archive.

Detail of "Reclamation" (2026). Hair, clay, paper, and other media

"Reclamation" (2026) installed at UMB Archive. Hair, clay, paper, and other media

"Reclamation" (2026) installed at UMB Archive. Hair, clay, paper, and other media

The doll has been placed inside the coffin, which is where it shall remain.

Gel stained coffin

The casket is close. The head piece (currently missing in this image) will be white oak to match the base.

Jay Allard, my collaborator built a white oak base using traditional joinery techniques. Here are the feet where the post will be inserted.

The base in-progress. The hatches show where the joinery cuts will be made on the post, which will be inserted into a base.

Handmade paper hibiscus flower, common in the global south and the national flower of Sudan.

One petal of a paper hibiscus flower.

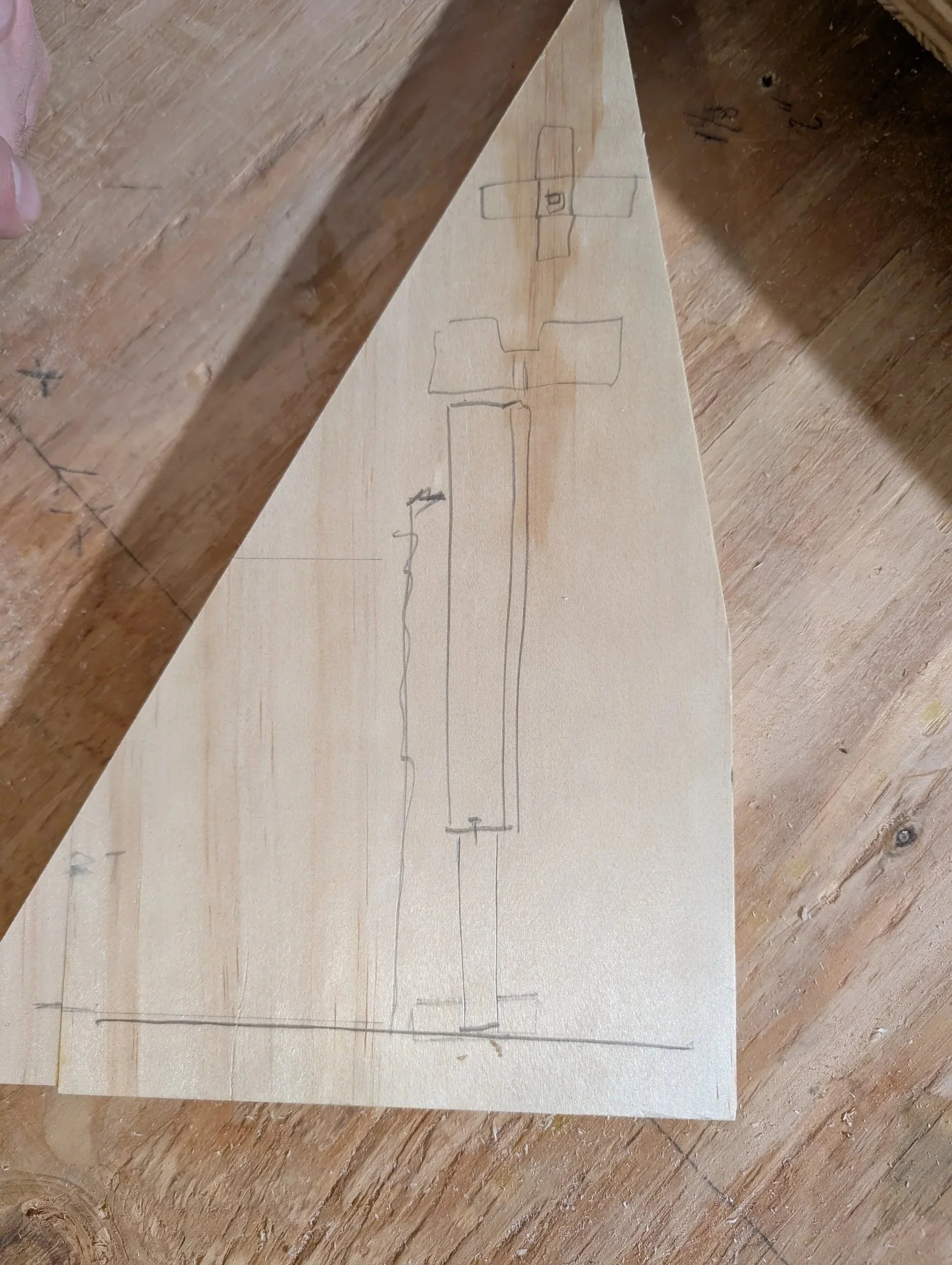

Notes on how to construct the base.

Checking the scale of the coffin to ensure the doll will fit properly.

The glued together coffin bottom

The back and front of the coffin are constructed from three planks of pine which are pegged and glued together, then sanded.

About Theresa-India Young, Fiber Artist & Educator

This first pieces in the Rest for Tired Negroes series recognizes Theresa-India Young (1950–2008), a fiber artist and educator.

As an Artist-in-Residence working with the UMass Boston Archives, I engaged with Young’s papers and objects, gaining insight into her process, values, and deep commitment to teaching. I understand her teaching as an act of continuity—expanding ancestral knowledge and carrying it forward.

My interaction with her archive continues that lineage. In many West African traditions, one remains alive as long as their spirit is remembered and passed on. My research surfaced recurring themes of hair, fiber, locks, knots, and symbols of labor embedded in craft. I searched for common threads between us—our shared African American heritage, time spent in a S.C. Gullah Geechee community, our roots as native New Yorkers, and a mutual commitment to creative community-building.

Birth Certificate of Theresa-India Young. (UMass Boston Archive)

Brick Baptist Church -- I took this photo during a 2024 trip to St. Helena Island, SC. The brick shows the working fingerprints of an enslaved African person who built the structure.

Lock of hair from Theresa-India Young (2006). (UMass Boston Archive)

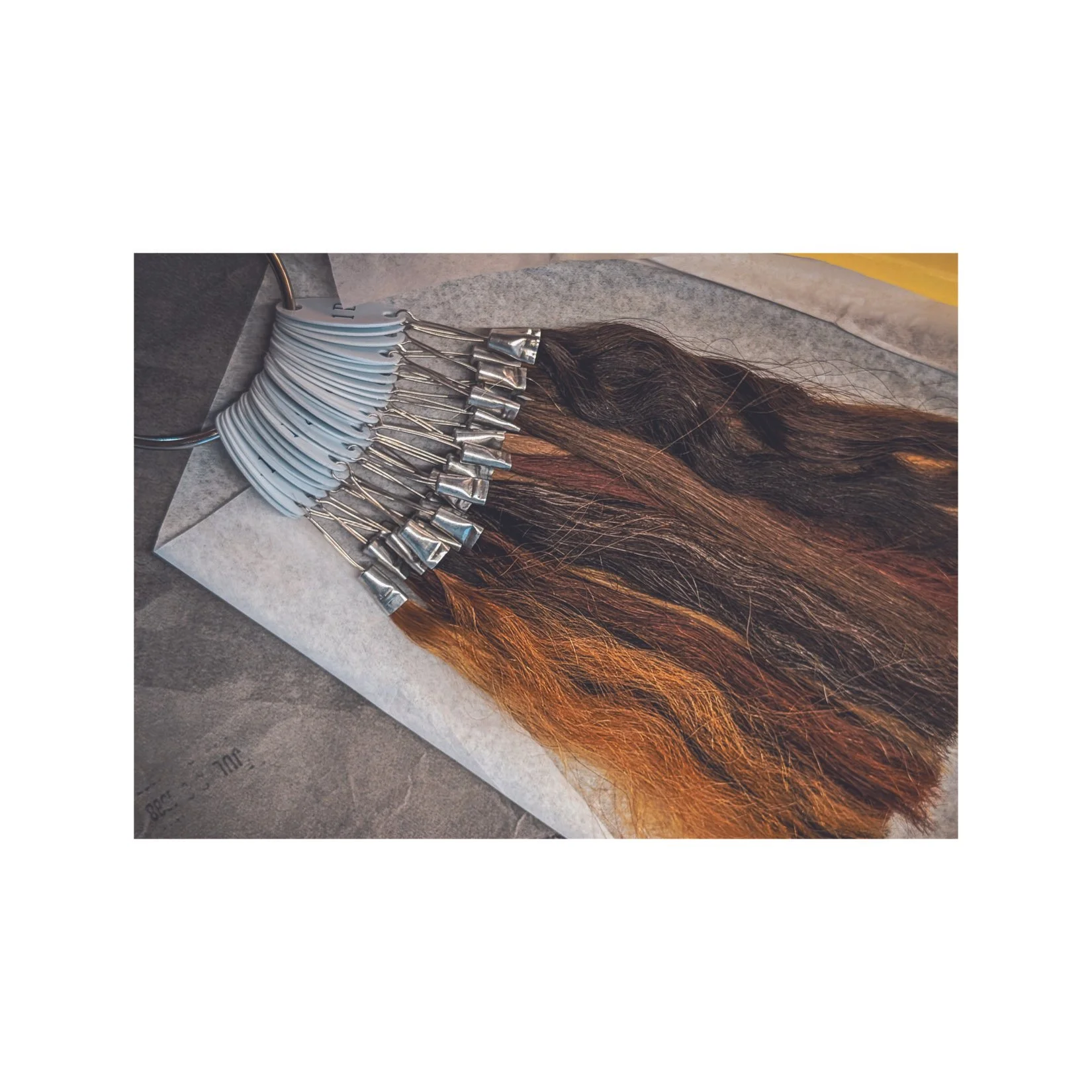

Theresa's collection includes samples of hair which she used in her art and broader craft projects. (UMass Boston Archive)

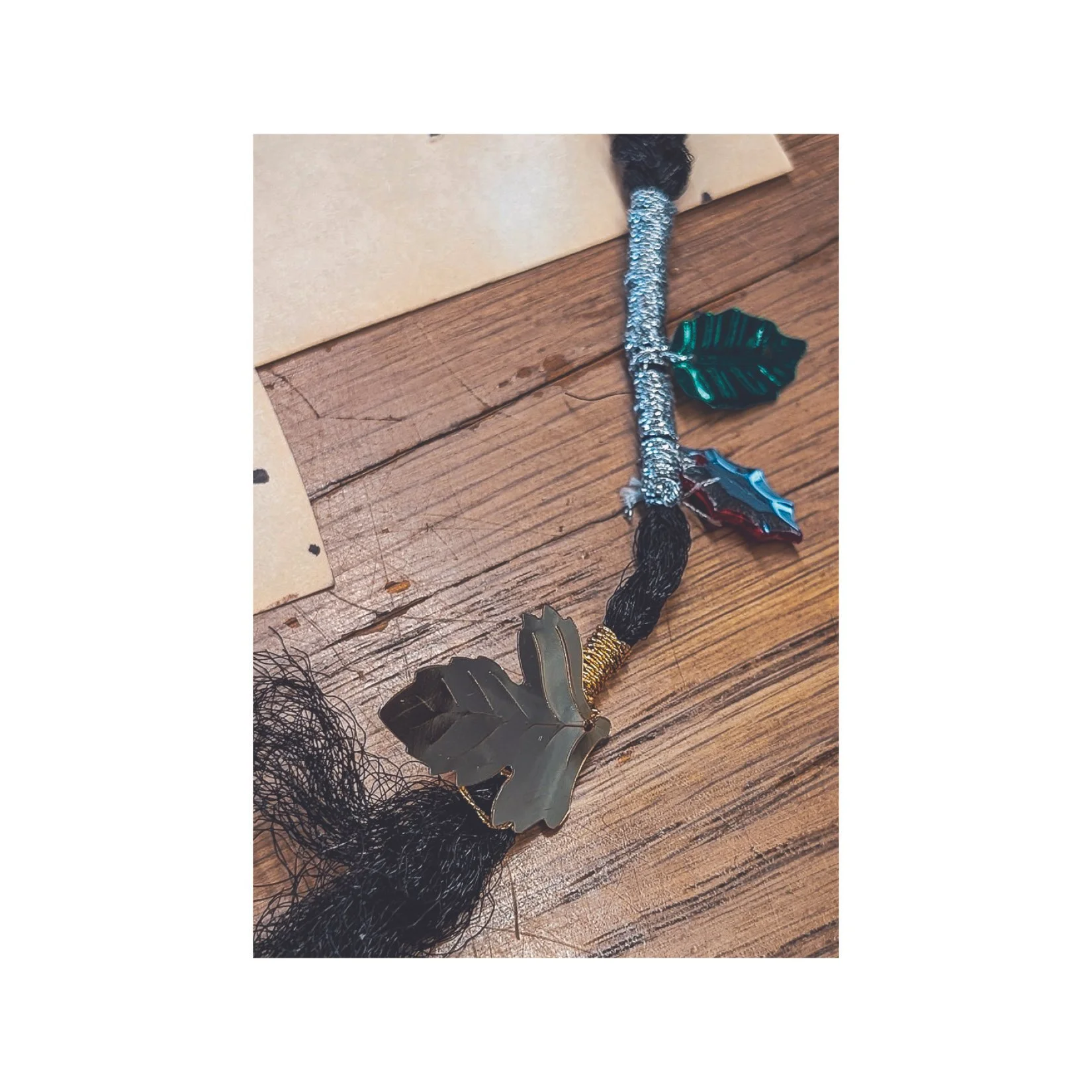

My dreadlocks which I cut in 1999. I've carried them with me since and am just discovering their purpose (outside of sitting on my head)

Theresa's collection includes samples of hair, which were used to show examples of hair wraps she offered for sale. (UMass Boston Archive)

This photograph was taken at the funeral of Theresa’s grandmother, Bernice Jackson. I have edited out the deceased out of respect for her and her family. (Sourced from the UMass Boston Archives)

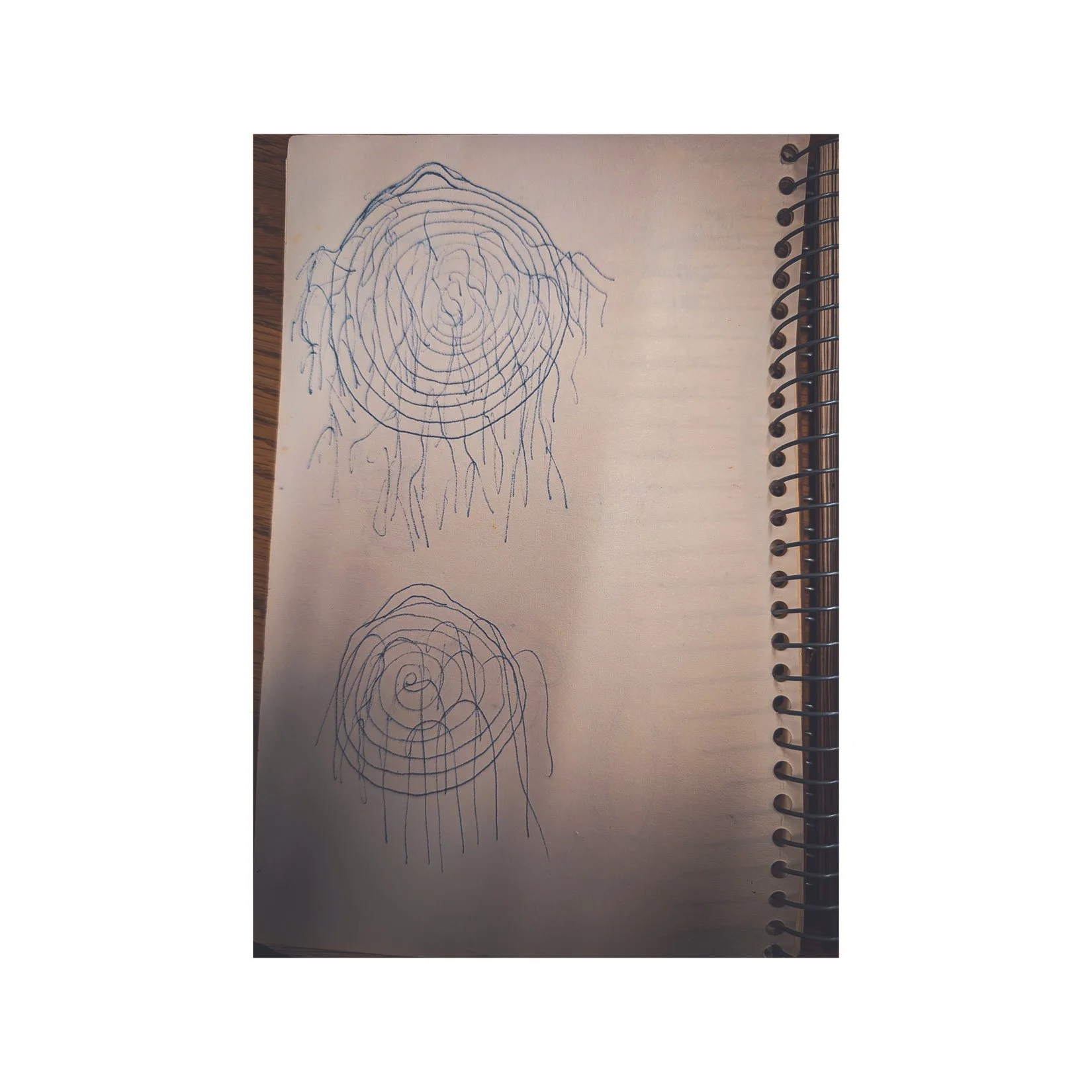

Images from Theresa's sketchbook feature organic forms, fiber art ideas. (UMass Boston Archive)

Images from Theresa's sketchbook feature organic forms, fiber art ideas. (UMass Boston Archive)

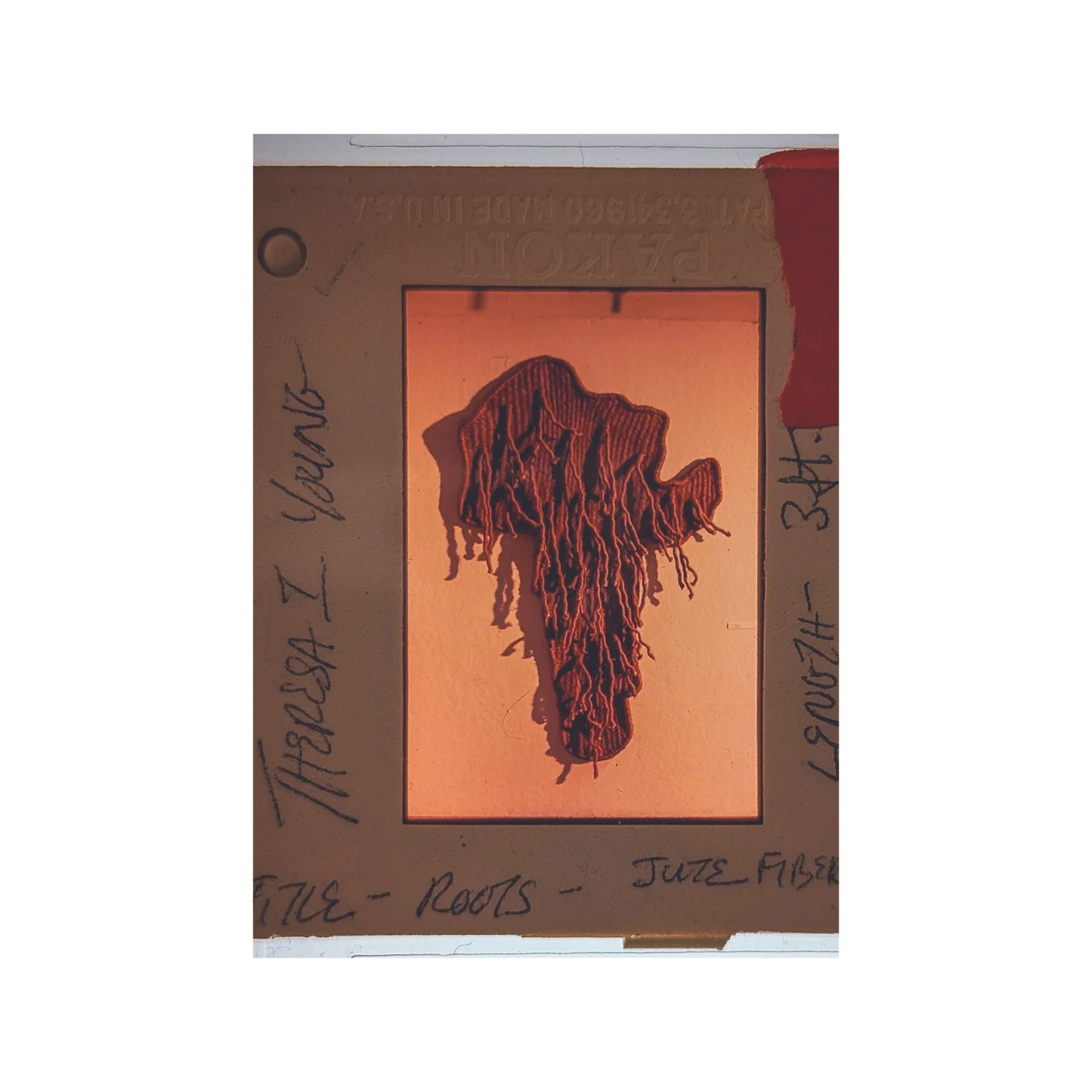

Slide of "Roots" by Theresa-India Young (UMass Boston Archive)

Slide detail featuring artwork by Theresa-India Young (UMass Boston Archive)

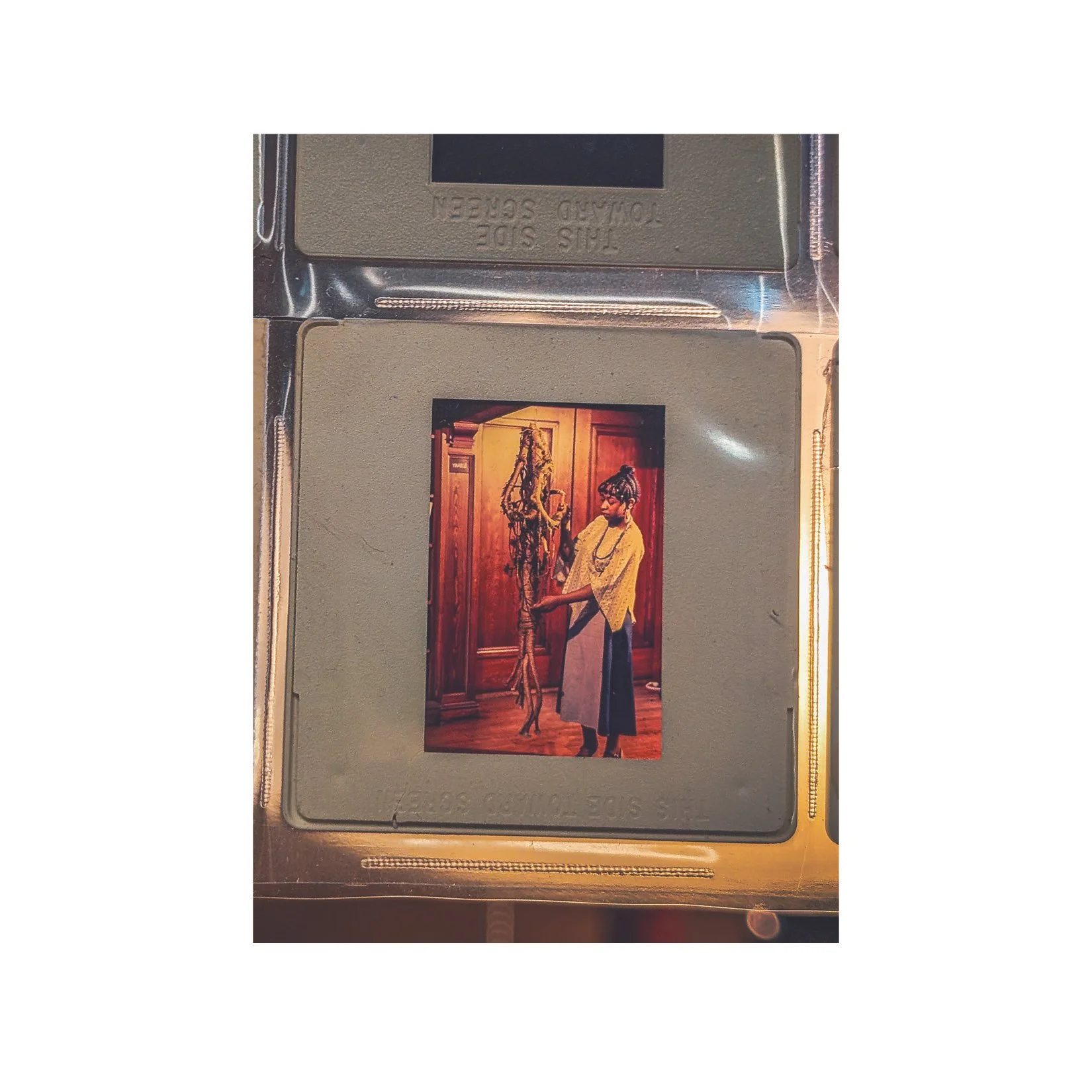

In this slide, Theresa stands beside here fiber art structure entitled "Tree." (UMass Boston Archive)